Primo quesito

Primo quesitoLa geometria euclidea è l'approssimazione utilizzata correntemente per descrivere il mondo su piccole scale. Aumentando la scala, ad esempio, bisogna considerare la curvatura della superficie terrestre, e per avere una geometria intrinseca abbiamo per forza bisogno di quella non euclidea. Aumentando ancora la scala, intervengono le correzioni della relatività generale, e anche per quelle è indispensabile la geomtria non ecuclidea.

Secondo quesito

Sia

, quindi

.

Se

, la distanza tra P e A è

d(x) = \sqrt{(x - 4)^2 + (\sqrt{x} - 0)^2}

= \sqrt{(x - 4)^2 + x}

= \sqrt{x^2 - 7x + 16}.

[/math]

Per trovare il minimo deriviamo:

d'(x) = \frac{1}{2 d(x)} (2x - 7) = 0

\quad \Longrightarrow \quad x = \frac{7}{2}.

[/math]

Quindi il punto P più vicino ad A è

Terzo quesito

\lim_{x \to a} \frac{\tan x - \tan a}{x - a}

\stackrel{\text{H}}{=}

\lim_{x \to a} 1 - \tan^2 x = 1 + \tan^2 a

[/math]

Poniamo

, allora

:

\lim_{t \to 0} \frac{\tan(t + a) - \tan a}{t}

= \lim_{t \to 0} \frac{1}{t} \left[ \frac{\tan t + \tan a - \tan a + \tan t \tan^2 a}{1 - \tan t \tan a} \right]

[/math]

= \lim_{t \to 0} \frac{\tan t (1 + \tan^2 a)}{1 - \tan a \, \tan t}

= \lim_{t \to 0} \frac{\tan t}{t} \cdot \frac{1 + \tan^2 a}{1 - \tan a \, \tan t}

= 1 + \tan^2 a

[/math]

Quarto quesito

\binom{n}{4} = \binom{n}{3}

\Rightarrow \frac{n!}{4!(n-4)!} = \frac{n!}{3!(n-3)!}

[/math]

,

Quinto quesito

consideriamo la seguente applicazione

\varphi:\mathbb{N}\rightarrow Q^{2}\\

[/math]

dove

Q^{2}=\left\{ n^{2}:n\in\mathbb{N}\right\}\\

[/math]

definita da

\\\varphi\left(n\right)=n^{2}\varphi\left(n\right)=n^{2}

[/math]

tale applicazione è iniettiva e suriettiva

biiettiva. Pertanto possiamo "contare" tutti i quadrati

\begin {array}{c|c|c|c|c|c|c}

\mathbb{N} & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & \ldots \\Q^2 & 0 & 1 & 4 & 9 & 16 & \ldots \end{array}

[/math]

e questo mostra che i quadrati sono tanti quanti i numeri naturali

Sesto quesito

Il massimo si ha per

Settimo quesito

La probabilità di fallire tutte le prove è

, mentre la probabilità di azzeccarne esattamente una è data da

.

Il quesito chiede l'evento complementare a questo, quindi

=1 - \frac{13 \cdot 3^9}{4^10} \simeq 24.4%[/math]

Ottavo quesito

il problema della quadratura del cerchio consiste nel costruire con riga e compasso un quadrato equivalente ad un cerchio dato. Il problema, in forma algebrica implica la risoluzione dell'equazione

(l=lato quadrato r=raggio circonferenza) e non ha soluzione a causa della trascendenza di

(la soluzione algebrica è

)

Nono quesito

Se

è un punto di

siano

i vertici del triangolo rettangoo nel piano.

Allora

PA=\sqrt{\left(x-a\right)^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}}\\

PB=\sqrt{x^{2}+\left(y-b\right)^{2}+z^{2}}\\

PC=\sqrt{x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}}\\

[/math]

Ne segue

\begin{cases}

\left(x-a\right)^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}=x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}\\

x^{2}+\left(y-b\right)^{2}+z^{2}=x^{2}+y^{2}+z^2

\end{cases}[/math]

\begin{cases}

x^{2}+a^{2}-2ax=x^{2}\\

y^{2}+b^{2}-2by=y^{2}

\end{cases}

[/math]

da cui

x=\frac{a}{2},\qquad y=\frac{b}{2}

[/math]

e quindi

che è la retta passante per il punto medio dell'ipotenusa AB e perpendicolare al piano che contiene il triangolo

Decimo quesito

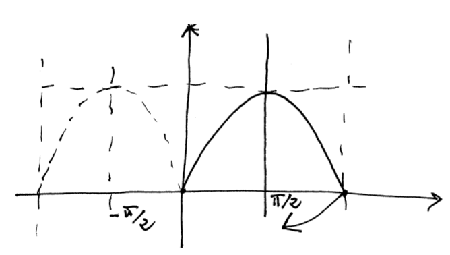

I grafici di I e III sono dispari, mentre II è pari. Poiché

g pari

g' dispari

g dispari

g' pari

ciò implica che f deve essere o I o III e f' è II. Poiché f' si annulla in due punti

f ha due punti stazionari e quindi un max e un min. Ne segue che f è la III e la risposta giusta è D

Accedi a tutti gli appunti

Accedi a tutti gli appunti

Tutor AI: studia meglio e in meno tempo

Tutor AI: studia meglio e in meno tempo